Flying Officer Gerald Hood (Navigator LM658)

1922-1945

“Gefusilleerd Door De Bezetter”

(Executed By The Invaders)

On the outskirts of the village of Zenderen, near to Almelo in the province of Overijssel, Eastern Netherlands, there is a path leading through the wooded area known as “De Vloedbeld,” should you ever walk this way you will come across an impressive bronze memorial statue in a clearing. Nearby are several white tablets laid in memory of local Dutch patriots who lost their lives resisting the Nazi occupation (1940-45), one of these tablets however, bears the name and date of birth of an R.A.F. officer and the chilling inscription as above.

On the outskirts of the village of Zenderen, near to Almelo in the province of Overijssel, Eastern Netherlands, there is a path leading through the wooded area known as “De Vloedbeld,” should you ever walk this way you will come across an impressive bronze memorial statue in a clearing. Nearby are several white tablets laid in memory of local Dutch patriots who lost their lives resisting the Nazi occupation (1940-45), one of these tablets however, bears the name and date of birth of an R.A.F. officer and the chilling inscription as above.

This is his story:

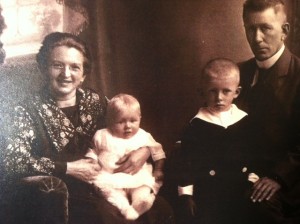

Gerald Hood was born on 25/02/22 in Lewisham, south east London, the son of Robert Washington Hood, a warehouseman in the drapery/hosiery trade and Emily Ellen Hood. His early life was tragic, by the age of eight his mother had died and his father also passed away soon after. So in 1930 under the sponsorship of a benevolent local company he was enrolled as a boarder at the Royal Russell School in Croydon, formerly a school for orphans and under privileged children of families from the drapery trade, which today is a top rated public school. Gerald Hood is well remembered by his contemporaries at the school, (some of whom are still alive at the time of writing in 2006) as popular and full of fun. Whilst at the school he flourished and his education progressed well, when once again, misfortune struck. In 1938 at the age of sixteen he was struck down with typhoid during an epidemic in the Croydon /Addingham area, luckily he made a full recovery. Hood left school to start work in the furniture trade as a sales assistant for Payne Brothers of Lewisham.

After the outbreak of war, at the age of nineteen, Hood enlisted in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) at the Euston recruiting office on 13/06/41 where he was recommended for training as an observer. The basic training of AC/2 1392236 Gerald Hood commenced at Catterick on 27/09/41 and over the next couple of years he made his way through the training process, some of which took place in South Africa. At the end of his training period on 22/02/44, just before his twenty second birthday Flt/Sgt Gerald Hood was posted from 1656 Heavy Conversion Unit at Lindholme to 101 squadron (1 group) at Ludford Magna as an operational navigator. Unfortunately, he was never to fly operationally with this squadron, he spent his time at Ludford Magna as a “spare bod” awaiting a permanent crew. Eventually late in April he was posted to 625 Squadron (1 group) at Kelstern and joined the already established crew of Flt/Sgt J.H. Burford as a replacement navigator.

On the night of 27th /28th April 1944 Gerald Hood flew on his first operation in Lancaster ED 938, to Freidrichshaven. Another twenty-two operational trips over occupied Europe would follow with this crew including the notorious raid on the massive German garrison at Mailly-le-Camp in France when heavy aircrew losses were sustained. Hoods’ twenty third operation to Tours, France on the night of the 12th /13th July 1944 was to be his last one with this crew, as they had almost completed their tour and were due to be screened off operations. For reasons unclear, two nights later Hood was replaced for their last operation to Revigny France. Burford, (now a Pilot Officer) and his crew returned safely to complete their tour.

Yet again, this left Gerald Hood as a “spare bod” and he had to wait for two weeks for his twenty forth operation to Stuttgart as a replacement navigator for the crew of P/O A.H.C Atkins on Lancaster PD100.

In the meantime, Hoods’ commission came through and on 02/08/44, Pilot Officer 178869 Gerald Hood was posted to 100 Squadron (1 group) at Waltham near Grimsby. Here he would join an established crew who had been operational with 100 Squadron since May. The men whose names would soon become associated with Gerald Hood for all eternity were;

Pilot – Flt/Lt Harold (Bill) Paston-Williams of Dorking, Surrey.

Bomb aimer – P/O Benjamin Ramsden of Bradford, Yorkshire.

Flight engineer– Flt/Sgt John Downie of Kilmarnock, Ayrshire.

Wireless operator– Flt/Sgt Laurence Roy Watts of Fawler, Oxfordshire.

Mid upper gunner – Flt/Sgt Robert Stanley Williams of Queensferry, Flintshire.

Rear gunner – P/O Bruce Arnold David (R.C.A.F). of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Click here for more crew list details

The crew’s original navigator Pilot Officer Carl Woodworth RCAF, (who was by this time a personal friend of the  Paston-Williams family) had been with the crew since training but had been posted back to Canada after completing eleven op’s. P/O Woodworth’s temporary replacement, Pilot Officer L.H. Gladman had just been screened on completion of his second tour and posted to No 8 (pathfinder) group for controller duties. So once again Hood found himself in the unenviable position of “new boy” as replacements were usually regarded as bad omens by established crews that had already bonded. To make matters worse Paston-Williams and his crew, who were already over two thirds of the way through their first tour were also waiting for a replacement aircraft. LM 585, HW-S (S-SUGAR) the one in which they had successfully completed the majority of their operations had recently been lost with another crew over northern France on a raid against a V1 rocket storage site. LM 585 was caught in heavy flak over the target and went down near Haversquerque, one parachute was seen to open, but all were reported killed, bad omens indeed! Hood did not have long to wait, just three days later on 05/08/44 having barely had time to get to know his new comrades he was to fly on his twenty-fifth operation, in Lancaster ND 639, a daylight raid on the Pauillac oil refinery, near Bordeaux, France. After a highly successful raid ND639 was diverted to land at Lindholme because of poor visibility at Waltham, to where they returned the following day.

Paston-Williams family) had been with the crew since training but had been posted back to Canada after completing eleven op’s. P/O Woodworth’s temporary replacement, Pilot Officer L.H. Gladman had just been screened on completion of his second tour and posted to No 8 (pathfinder) group for controller duties. So once again Hood found himself in the unenviable position of “new boy” as replacements were usually regarded as bad omens by established crews that had already bonded. To make matters worse Paston-Williams and his crew, who were already over two thirds of the way through their first tour were also waiting for a replacement aircraft. LM 585, HW-S (S-SUGAR) the one in which they had successfully completed the majority of their operations had recently been lost with another crew over northern France on a raid against a V1 rocket storage site. LM 585 was caught in heavy flak over the target and went down near Haversquerque, one parachute was seen to open, but all were reported killed, bad omens indeed! Hood did not have long to wait, just three days later on 05/08/44 having barely had time to get to know his new comrades he was to fly on his twenty-fifth operation, in Lancaster ND 639, a daylight raid on the Pauillac oil refinery, near Bordeaux, France. After a highly successful raid ND639 was diverted to land at Lindholme because of poor visibility at Waltham, to where they returned the following day.

That same week, a new aircraft had been delivered to Waltham from the factory at Yeadon near Leeds, A Lancaster Mk III serial number LM 658, it was given the squadron identity code of HW-W. This aircraft went straight onto operations with another crew but on her maiden flight to France she had to abort due to poor visibility making the target impossible to identify. LM 658’s second raid was also to France, to the railway marshalling yards at Douai near Lille, which was completed successfully.

On 09/08/44 Flt/Lt Paston-Williams and his crew performed their first air test on LM 658, for this was to be the replacement aircraft that would, maybe, carry them through to the end of their tour. Their next raid would be Hoods’ twenty sixth, so he too was approaching the end of his first tour of thirty operations. Although, as indicated by Flt/Sgt Watts in his last letter, dated 11/08/44 to his sister Mrs Denise Pilfold, the crews were now aware that a tour may about to be extended to a total of thirty five operations.

They did not have to wait long to take LM 658 over occupied Europe. On Saturday 12/08/44 at 2145 hrs, they took off from RAF Waltham along with six other Lancasters as part of the second wave of a total formation of 379 aircraft en route for the manufacturing and communications hub of Braunschweig, (Brunswick) Germany. At the controls, alongside Flt/ Lt Paston-Williams was Flt/Lt Christopher Holland, aged twenty-one from Horsham Sussex on his “second dickie” (familiarisation trip). With the exception of the C/O, Wing Commander R.V.L. Pattison and his crew, each 100 sqdn aircraft carried a “second dickie.” However, only six of the seven aircraft that took off from Waltham on that warm August night were destined to return home safely on the following morning.

The raid itself was essentially an experiment, as no pathfinder force would be used to drop marker flares. The intention was to see how accurately a target could be hit with each individual crew using its own “H2S” direction finding equipment. Conditions were ideal for such an operation as 10/10ths-cloud cover was forecast over the target. Aboard LM 658, Hood, as navigator would have played the key role in the operation of the”H2S” system. Overall, the experiment was not as successful as planned; later reconnaissance reports state that an effective concentration of bombing was not achieved.

LM 658 and the other six aircraft from 100 Sqdn, formed up off the Lincolnshire coast and joined the bomber stream as part of the second of three waves. The second wave aircraft were all from 1 Group, a total of 127 bombers who would fly the most southerly route to the target passing between the Fresian Islands of Vlieland and Terschilling, where as usual, the ground defences were active, the raid was being plotted and the German ground controllers were now expecting them, though still unsure as to where the target would be. The second wave crossed the Dutch coast near Harlingen, keeping well to the south of Leeuwarden and on to the next turning point near Emmen, here the German controllers incorrectly identified the target as Bremen and vectored the night fighters accordingly, the first wave from 5 Group had taken a similar route, but more to the north, indicating Bremen as the likely target. The feint had worked and saved the first two waves from the onslaught of fighters, 4 and 6 Groups in the third wave would bear the brunt when the ground controllers realised their error as the first two waves then dog-legged to the south of Hanover to approach Braunschweig from the south west.

However, all was not well aboard LM658. As they were approaching the Dutch coast, Hood broke the news that both “Gee” and “Y” radio navigation aids were inoperable, they were experiencing strong winds and they were off course, leaving Paston-Williams with the decision to abort and turn for home or to press on. Turning round and returning to Waltham against the bomber stream was discounted as an option, also an early return would not count as a completed op, so they pressed on for the target. With dead reckoning from Hood as navigator and Ramsden spotting pin-points from his bomb aimer’s vantage point in the nose they managed to maintain a course, despite suffering two heavy flak hits whilst on the run in to the target, luckily without any crew casualties.

Overcoming their technical problems using basic navigation techniques, they located the target area and commenced the bombing run, running the wholly expected gauntlet of heavy flak and a wall of searchlights, when yet again they took another hit from flak. Cloud cover was heavy but Ramsden managed to get a sight on fires burning below and at 0005hrs, not much later than planned, Ramsden called “bombs gone” as he released their bomb load of high explosives and incendiaries. LM 658, relieved of her bomb load and now feeling much lighter turned for home, but was hit once again by flak as she left the target area. Navigation was still proving difficult in the high winds and without their direction finding equipment, again Hood realised that they were off course. They got a fix and realised that they were just to the south of Hanover rather than to the east of the city on the planned return route, when once again they started taking ground fire and were hit hard by another flak burst, which penetrated the inner starboard fuel tank, they were now on fire, which quickly spread to the cross-balance pipe, leaving Downie with few options to transfer and conserve vital fuel. Realising that they were in trouble, Paston-Williams first instinct was to try and keep her in the air long enough to get out of German airspace and at least reach the Dutch border, where help on the ground would be more readily available.

They flew on, but unfortunately, the glow from the blazing fuel tank left them very visible in the night sky and wide open to attack from the prowling night fighters that were bound to be in the area! Meanwhile Downie the flight engineer was attempting to move aft with a fire extinguisher but was met by the navigator, wireless operator and mid-upper gunner moving forward, with ‘chutes on to escape the flames from the fuel fire and the fumes from the electrical accumulators also now ablaze, ammunition from the mid-upper turret was also starting to explode. Downie now realised that the fire was beyond control and signalled as such to the second pilot. Then the attack came, the Canadian, Bruce David in the rear turret spotted the sinister twin engined shape below and shouted for “corkscrew” so Paston-Williams kicked the rudder hard and pushed forward on the control column, sending LM658 into a steep dive. Luftwaffe records from this night show a possible claim came from Feldwebel Robert Koch and his observer of 6/NJG 1 flying a Messerschmitt BF110G out of St Trond, Belgium. Whilst on patrol to the north east of Enschede at an altitude 5000m they reported an engagement with a burning four engined bomber at approx 0105hrs. In the heat of battle the gunners mistakenly identified the attacking aircraft as a Messerschmitt Me 410, but subsequent research has proved that no Me 410’s were operational in the area on that night.

After two minutes of violent evasive action in an aircraft that was already on fire the rear gunner called to resume course as he had lost sight of the attacking fighter. What happened next could be measured in a timescale of seconds but must have felt like a lifetime, as LM658 levelled out, the crew all felt the thump of cannon shells hitting the fuselage from behind and below. The German pilot had managed to shadow them unseen into the corkscrew. Paston-Williams glanced to port and saw a stream of tracer just missing the wing and immediately took evasive action, throwing her to starboard, and pulling back hard on the column, but the control surfaces were no longer responding properly and the airframe, weakened by the fire finally failed and the whole tail section of the aircraft broke away. Realising all control was lost, Paston-Williams signalled the order to abandon, as by now all contact had been lost via the intercom due to electrical system failure.

Ramsden, being nearest to the barely adequate front escape hatch forced it open and jumped, followed by Hood, Holland and Williams (in what order will never be known) At this point the aircraft exploded, broke up and lurched over into its final fall to earth. The rear-gunner, David, cut off by flames and exploding ammunition had successfully exited from the rear of the aircraft. Paston-Williams and Downie were both blown clear and knocked unconscious, but Watts the wireless operator, fighting for his life against the powerful forces of gravity as he tried to make his way to the front hatch, sadly never made it out and was carried down with the nose section of the disintegrating bomber. Had he hesitated to see if Bruce David was still trapped in the rear turret? We will probably never know for sure.

John Downie was semi-conscious and falling head over heels through the night air, he quickly came to and realised that his parachute harness was only half fastened, he managed to pull the rip-chord and regain his senses, from which point he had a clear view of the burning wreckage of LM658 falling to earth. Downie then saw, illuminated by exploding signal flares ejected from their aircraft, two parachute canopies billowing far below him, which would most likely have been Paston-Williams and Hood. Paston-Williams was very lucky indeed, blown out of the aircraft at the same time as Downie, he had free-fallen much further, regaining consciousness just in time to pull his chute, landing almost immediately in a soft peat bog. No further ‘chutes could be seen, Bruce David was well out of Downie’s line of sight having exited from the rear of the aircraft and for reasons that we can only speculate about; Ramsden, Holland and Williams, despite successfully exiting the aircraft had somehow been knocked unconscious, their bodies were all found within 500ft of the wreckage, ‘chutes on but unopened. They had come down just over the border in occupied Dutch territory on farmland north of Almelo, between the villages of Hardenberg and Bergentheim at approximately 0110 hrs local time, on the morning of 13/08/44.

The body of Laurence Watts was found under the wreckage, during recovery operations in the following days, local police reports state that he was half way out of the escape hatch with his parachute on. The four comrades who died that night are interred together in the Hardenberg Protestant cemetery alongside many other allied airmen who met a similar fate. They remain in the perpetual care of the Dutch people and the commonwealth War Graves Commission. Paston- Williams, Downie and Hood would be picked up by the local Dutch partisans later in the morning, David, despite being approached by friendly Dutch locals was unsure of who to trust and continued to evade until captured and arrested, to become a Prisoner of War.

Hood meanwhile, had landed safely but in escaping from the burning aircraft he had suffered serious burns to his legs. Alone, in shock and unsure of his exact position, he was soon found by Jan Piksen, a local resistance leader well practised in locating and containing aircrews soon after they had bailed out. So fortunately for Hood he was now safely in the care of the local underground network who did the best they could to provide him with medical attention, shelter and civilian clothes. Soon after rescuing Hood, Jan Piksen was betrayed, ambushed and shot dead near Haarle whilst attempting to make contact with another newly baled out crew. Over the next few days Hood was moved to the nearby village of Nyverdal to an established safe house, the home of M. Ebeltje van der Wal, a widow who lived with her twenty three year-old daughter Grietje. After a week it was decided that it would be safer if Hood was moved to the home of the Ter Avest family on the outskirts of nearby Rjissen. Here he stayed until 01/01/45, when it was decided that Nyverdal was again a safer area and at the request of M. van der Wal, Gerald Hood returned.

It should be noted that documentary evidence suggests that during this period allied aircrew were actively discouraged by the Dutch underground from heading west and trying to cross the Rhine. It was considered an unnecessary risk to both airmen and resistance members because of heightened enemy activity in the area due to the advance of allied forces now well under way. Optimism was high and liberation was expected soon, so it was considered that the best option for downed aircrew was to lie low and wait for the allied advance to overrun the area, so Hood settled in to life in occupied territory with a family that treated him as a son. One can never overstate the bravery and compassion shown by families such as the van der Wals. Taking in allied airmen and sheltering them in your own home, within your own family whilst living under occupation, with the constant threat of discovery and the inevitable dire consequences must have required the purest form of courage and fortitude. Meanwhile, back in England on 28/12/44 Gerald Hoods’ promotion to Flying Officer was posted in the London Gazette in his absence.

As well as her daughter Grietje, M. van der Wal also had a son called Bote (pronounced “Bert”), he was twenty-one years old and before the war had been a French language student. Bote van der Wal had been a fugitive from the authorities for over two years after refusing to sign loyalty papers to the Nazi regime and join the labour programs, but according to his mother he was not an active member of the resistance.

On the night of 13/03/45 Bote van der Wal was at his mothers’ house, it had been his birthday and they had held a small party for him. Unfortunately Bote’s presence had been noted by a local Nazi sympathiser who reported this to the authorities. At about 0130hrs the house was surrounded by a detachment of the Almelo SD under the command of a Hauptman Bakker (The SD was the local SS Police Division which included both German and Dutch nationals) they had come for Bote. They entered the premises and after an extensive search lasting almost three hours they still had found nothing. Although well concealed, Bote Van der Wal and Gerald Hood decided to surrender themselves when they feared for the safety of the women. Having identified Bote they were at first confused as to the identity of Gerald Hood, until they discovered his service identity tags. The SD unit was elated at their discovery so both men were arrested and escorted at gunpoint on bicycles to Almelo jail.

It should be noted that M. van der Wal, despite being the owner of the safe house was fortunately and somewhat curiously never arrested for harbouring the two fugitives. This was possibly an oversight on the night with the SD pleased at having caught a long time Dutch fugitive and a downed allied airman all in one go. Over the next few weeks however, as the allied advance swept towards the area, M. van der Wal would have become a very low priority!

Over the next week, Oberfeldwebel Georg Otto Sandrock, who spoke good English, interrogated Hood. This was carried out under the orders of SS Untersturmfurher Paul Hardegan, the commander of the local SD and a dedicated Nazi with a reputation for brutality to prisoners.

SD staff (Almelo Division) 1944. SS Untersturmfurher Paul Hardegan is seated front row, second from right.

Until recently, the local commander of the SD had been Hauptsturmfurher Dr Oskar Konrad Gerbig, he was known as being relatively humane in comparison to his successor, but under his supervision many atrocities were carried out regardless. After the war, Gerbig was tried and sentenced to twenty years in prison but released in 1957.

During his interrogation, Hoods’ own account of his movements did much to protect those who had helped him over the last few months, but little to help his own situation. He stuck to his story that he had been shot down only recently near to where he had been captured at Nyverdal and was unable to remember were he had hidden his parachute and uniform in the dark. Sandrock checked the local records and concluded that Hood could not be telling the truth as no aircraft had come down in the area at, or even near the date and time that he had indicated, which was not actually correct.

During their time in Almelo prison, both Bote van der Wal and Gerald Hood were able to get messages to each other and to the van der Wal family via one of the prison guards. Jan Veldhuis was a Dutch patriot who acted as the man on the inside for the local resistance. It was clear from these messages that Hood was under the impression that he was about to be transferred to a prisoner of war camp. At 0900 on the morning of 21/03/45, Untersturmfurher Paul Hardegan entered the office of Sandrock and announced that the Gerald Hood had been condemned to death as a spy and the execution should be carried out without delay that very evening. At first Sandrock was shocked and concerned that no proper trial had taken place, as it was obvious to him that Hood was indeed a captured airman, but orders were orders and he was not prepared to challenge the will of his superior. So that afternoon Hood was transferred from Almelo Prison to the office of Sandrock where he was held for the rest of the day, still under the impression that he was about to be transferred to a P.O.W. camp.

At about 2200 that evening under the command of Georg Otto Sandrock, a German staff car left Almelo and proceeded along the road in the direction of Borne to the village of Zenderen. In the car with Sandrock were Gerald Hood and two German SD policemen; Ludwig Schweinberger and Franz Josef Hegeman, Schweinberger (who had volunteered to carry out the execution) was carrying a 9mm pistol issued to him by Hardegan. On the outskirts of Zenderen the car made a right turn and came to a halt at the edge of the woods. Here, Hood was told to get out of the car and walk down the path towards the woods, followed by Sandrock and Schweinburger. Hegeman, who repeatedly stated at the subsequent trial that he was “very unhappy to be involved” stood guard by the car. As they started to walk Sandrock informed Hood that he had been sentenced to death. Hood uttered something in English, that Sandrock later stated that he did not understand, these were the last words of a twenty three year old English officer, we can only hope that he chose them well. Schweinberger raised the pistol and fired one shot into the back of Hood’s neck at the base of his skull. They checked that he was dead and removed his watch then unceremoniously dragged his body further into the woods where it was stripped and buried in soft earth close to a bomb crater. Two days later, Bote van der Wal met the same fate as his friend Gerald Hood in exactly the same spot.

Tragically, within two weeks the towns of Almelo and Hengelo were overrun and liberated by British and Canadian forces. In Hengelo Flt/Lt Harold (Bill) Paston-Williams and Flt/ Sgt John Downie were also liberated and soon on their way home to the UK.

Liberation day in Hengelo, Harold Paston-Williams is extreme right, middle row, wearing a beret. John Downie is fifth from the left, front row, in hat and light raincoat. Second from the left, front row, in a light raincoat is Roy Fellows, rear gunner of ME732 the 61Squadron Lancaster that crashed on Almelo in Sept 44.

Liberation day in Hengelo, Harold Paston-Williams is extreme right, middle row, wearing a beret. John Downie is fifth from the left, front row, in hat and light raincoat. Second from the left, front row, in a light raincoat is Roy Fellows, rear gunner of ME732 the 61Squadron Lancaster that crashed on Almelo in Sept 44.

The other survivor from LM 658, Pilot Officer Bruce Arnold David, the Canadian rear gunner had been captured soon after the crash and was to survive the war after being held in a P.O.W. camp, Stalag Luft I at Barth, near to Rostock, on the Baltic coast.

Later that year, in August, the Dutch authorities, along with local resistance men and investigating officers from the United Nations War Crimes Commission located and exhumed the bodies of Gerald Hood and Bote van der Wal. Hood was re-interred in the Almelo town cemetery under the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, near to a number of British and Commonwealth soldiers who, but for a few days, would have been part of the force that liberated him. Alongside Gerald Hood, in the well tended cemetery lie six of the crew of a 61 Squadron Lancaster (ME 732) which crashed on Almelo in September 1944. The surviving rear gunner from this aircraft Flt/Sgt Roy Fellows was sheltered in Hengelo along with John Downie and Harold (Bill) Paston-Williams.

Eventually Sandrock, Schweinberger and Hegeman found themselves in the custody of the allied forces and in November 1945 stood trial for murder at the courthouse in Almelo under the authority of the U.N. War Crimes Commission. Despite their defence plea of following superior orders they were all found guilty of murder, Hegeman, who kept watch by the car went to prison for 15 years, Sandrock and Schweinberger went to the gallows at Hameln on 13/12/45.

The whereabouts of S.S. Untersturmfurher Paul Hardegan who ordered the execution was apparently not known at the time of the trial, he made his escape from Almelo just prior to the liberation of the area, knowing full well that he would have to account for much if captured. He was last heard of in the Utrecht area, but by the time he had been sentenced in his absence, Hardegan had vanished for good. Evidence suggests that he was smuggled out of Europe and began a new life under a new identity.

Ludwig Schweinberger, executioner of Bote van der Wal & Gerald Hood. No known photograph – do you have one? Please contact the LM658 Webmaster.

After the end of the war in Europe and nearly one year and three months after his death Gerald Hood was mentioned in dispatches on 13/06/46 for protecting his Dutch helpers under interrogation. The MiD was published in the fifth supplement of the (June) London Gazette, so Gerald Hood posthumously received a single oak leaf to accompany his 1939-45 Star, France & Germany Star & WWII Medal.

In addition to the memorial in the woods at Zenderen, his burial plot at Almelo general cemetery and the 100 Squadron roll of honour, Gerald Hood is commemorated in the following places:

Royal Air Force Book of Remembrance,

Church of St Clements Dane,

The Strand,

London.

Royal Air Force (1 group),

WWII Roll of Honour,

Lincoln Cathedral.

St Christopher’s Chapel (and Garden),

Royal Russell School,

Croydon,

Today Almelo is a busy, friendly, modern town with strong links to the UK, twinned with the City of Preston Lancashire. The original frontage of the former Police station and prison in Marketstraat remains; it is now a combination of shops, offices and private dwellings. If you head out towards Zenderen, follow the signs to the “Oorlogsmonument” (war memorial), along the path through the woods into the clearing. Here you will find the bronze statue in a very peaceful wooded glade, but only those that have no soul will fail to be affected by the atmosphere that surrounds you.

Here, the public can pass freely, yet there is not a scrap of litter, the stone plinth that supports the statue bears no scrawled homage to some football team or rock band. So typical of the respect shown by Netherlanders of all ages to the memorial sites of all allied casualties of war. The monument site in the woods has been adopted for all time by the local children from the St Stephanus school in Zenderen and every year on Liberation day (5th May) a service of remembrance is held in the clearing in the woods for all those commemorated there including Hood, whose story, probably due to his orphaned status appeared to have been largely unknown, forgotten even, back home in the UK until recently of course.

Click for details of the Gerald Hood Memorial Day & the Conclusion to his tale.

This version of the Gerald Hood story is an adaptation (shortened but with additional information since come to light) of my own article that was published (Aug 2006) in “The Hornet” The newsletter of the 100 squadron Association.

Alan J Barrow