Sqdn/Ldr H ( Bill ) Paston-Williams A.F.C.

Aviator and Airman

By his son: Alan Paston-Williams

In the early sixties the blossoming business aircraft sector employed many ex WWll pilots, now into middle age but continuing to do the thing they loved – flying. Not infrequently a slumbering, disused wartime aerodrome found its tranquillity disturbed by the arrival of several brightly coloured corporate aircraft, disgorging their captains of industry and entourage to waiting limousines which crunched off around the crumbling peri-track, leaving their pilots to wander quietly through deserted hangers and dormant watch office. For us younger crew it was understood that there were memories that could not be shared with us for all the camaraderie of the air and in any case it was the sixties and we had lots of living to do, thanks to them! My dad was one of those men who would take a silent, reflective stroll with the ghosts of his past whenever the opportunity presented itself.

I grew up as part of this service family and although I flew with, worked with, often argued with (on the ground!) and helped nurse dad before his death on Christmas Day 1976 I had little knowledge of his early aviation career and in particular his World War II experiences. I was aware he had been shot down and survived thanks to the Dutch Resistance. More facts began to emerge when I found his complete set of flying log books which I read with great interest and eventually donated to the RAF Museum at Hendon as a record of one airman’s story.

Then a letter arrived from Stichting (1940 – 1945), an association relating to the wartime Dutch Resistance movement requesting confirmation that a Mrs. M.G.J. Baars-Kroeze had helped dad during the war, this I was able to verify via his records and the RAF Museum. After that letters and contacts kept coming from dedicated researchers both in Holland and the UK. Then followed contacts from former student pilots and researchers working on the story of Lancaster LM658 and her crew, who were particularly interested in the story of the navigator Flying Officer Gerald Hood, but this is Dad’s story, put together with the help of my sister Sheila, family memories, letters, mum’s war diaries, archives and as always the dedicated researchers.

Harold Paston-Williams – Hal to close family, PW to senior officers and Bill to the rest of the RAF and wider world was born in Cawnpore India on the 5th September 1911. He was followed by sister Sylvia in 1913 and brother Guy Elwyn in 1915. His father Frederick Paston-Williams was a Presidency Postmaster. Dad’s great grandfather had left Norfolk in 1841 enlisting in the army and sailing for India, he survived the horrendous second Sikh Wars and bought himself out from the 9th Lancers for £30 in 1847 joining the postal service, he, his family and the subsequent generations flourished in India.

At the age of 11 Dad was sent to Bishop Cotton School in Simla (motto; overcome evil with good), as was his younger brother Guy Elwyn Williams, He won an early claim to fame saving the life of a friend who had slipped over a cliff, holding on to him with one hand for 20 minutes until help arrived. He also excelled himself at boxing for the school and developed a love of hockey which stayed with him throughout his RAF career.

At some point his interest in flying was aroused, perhaps by early pioneering flights to India and on reaching his majority (21)  he was given a flying course at the Madras Flying Club, He went solo on 22nd June 1932 in a De-Havilland DH 80 Puss Moth after 10 hours and became the proud holder of aviators certificate number 332 issued by the Aero Club of India and Burma on the16th Nov 1932. Dad continued flying around India until the family decided to uproot and leave for England in 1934, a huge change for all of them as life was tough in the England of the 1930s, not to mention the weather! Dad worked as a commercial traveller and flew when he could afford it. On the outbreak of war dad enlisted in the RAF and after some delay he was selected for pilot training, his brother Guy joined the Royal Navy where he trained as a coder.

he was given a flying course at the Madras Flying Club, He went solo on 22nd June 1932 in a De-Havilland DH 80 Puss Moth after 10 hours and became the proud holder of aviators certificate number 332 issued by the Aero Club of India and Burma on the16th Nov 1932. Dad continued flying around India until the family decided to uproot and leave for England in 1934, a huge change for all of them as life was tough in the England of the 1930s, not to mention the weather! Dad worked as a commercial traveller and flew when he could afford it. On the outbreak of war dad enlisted in the RAF and after some delay he was selected for pilot training, his brother Guy joined the Royal Navy where he trained as a coder.

1940 was a momentous year for dad, on the 20th April that year he married Janet Lewis whose father AJ Lewis was a company director and lived at 10 Castle Gardens, Dorking Surrey, part of an 18th century stable block nestling between the bank of the River Mole and Betchworth Golf Course, this became the family home with the arrival of us twins, as well as a sanctuary for wider family, crew and colleagues, helped no doubt by the adjacent golf course and the 19th hole, avoiding the searchlight battery cluttering up the fairway and busy and dangerous skies above. I became an ardent plane spotter before being able to walk and caused much amusement toppling over backwards watching aircraft overhead. Castle Gardens was a refuge for illnesses, births and bereavement it also served as a “post box” both during and after the war. From here Mum joined that band of stalwart aircrew wives following their husband’s postings, packing and unpacking… and waiting.

1940 also saw the start of his pilot training at age 29, first to 5 Initial Training School at Nether Avon then on to Elementary Flight Training School. 1941 came and his training continued, on the home front mum noted on the 22nd Jan in her war diaries “Jerries over Salisbury, heavy bombing.” In May, he was posted to Ansty near Rugby where he found digs for mum, who on passing through nearby the recently destroyed city of Coventry noted “Coventry an awful mess.” In June, dad’s brother Guy got married. In October dad was posted to Perth in Scotland. On completion of his training dad was older than most so was trained for ab-initio (initial) instructing on De- Havilland DH 82 Tiger Moths and Miles Magisters, helping to train the growing number of RAF pilots coming through the system. In November mum was able to join him in Perth. 1942 started with long crowded train journeys down south and back in heavy snow, as postings came and were cancelled, in July he was posted to Weston on the Green to a glider unit.

1940 also saw the start of his pilot training at age 29, first to 5 Initial Training School at Nether Avon then on to Elementary Flight Training School. 1941 came and his training continued, on the home front mum noted on the 22nd Jan in her war diaries “Jerries over Salisbury, heavy bombing.” In May, he was posted to Ansty near Rugby where he found digs for mum, who on passing through nearby the recently destroyed city of Coventry noted “Coventry an awful mess.” In June, dad’s brother Guy got married. In October dad was posted to Perth in Scotland. On completion of his training dad was older than most so was trained for ab-initio (initial) instructing on De- Havilland DH 82 Tiger Moths and Miles Magisters, helping to train the growing number of RAF pilots coming through the system. In November mum was able to join him in Perth. 1942 started with long crowded train journeys down south and back in heavy snow, as postings came and were cancelled, in July he was posted to Weston on the Green to a glider unit.

Training those very brave men of The Glider Pilot Regiment was quite a challenge, by now “an above average instructor” he needed all of his skills to make sure that, sitting in tandem behind his student (not to mention the 6th Airborne Division troops in the back when carrying live loads), all survived the experience of “motorless” aircraft as the RAF called them. The description was apt as the Hotspur had its original specification changed and wingspan and gliding performance reduced, The Hotspur was only ever used as a trainer and was soon to be replaced by the more famous Horsa. The average flying time seems to have been about 10 minutes and with no chance of going around again if the student made a mistake and there was little protection from the flimsy aircraft, accidents and injuries were frequent. Mum by now had caught up with him again and “had Hal home with injuries“ on several occasions.

1943 started at No1 Gliding School at Croughton, then posted to No3 Advanced Flying Unit at South Cerney where he flew Oxfords, then on to 91 Operational Training Unit, Wymeswold.

Mum had returned to Castle Gardens, Dorking in May as she was now expecting their baby in June. As the time approached she sensibly moved to a nursing home in Dorking and on June 19th after some delay, I arrived followed 22 minutes later, much to everyone’s shock, by my sister Sheila! “Shocked but everyone thrilled” was the diary entry for that day followed by 14 days recuperation for mum. Dad managed 2 days with her then had to return to training. On the 30th June he wrote to say he had now got his crew, sadly with no names, I expect mum wrote back to remind him she had got hers as well!

Now flying Wellingtons he was being signed off on various courses including cross countries with live loads. During that June dad and his crew surviving 2 forced landings in 2 days! But they were now an operational crew, their first op was on Monday August 30th whilst still at the Operational Training Unit to Eperl le Foret in France, an “easy” one, however they were hit by flak and the port engine caught fire, luckily they made a successful forced landing at Bradwell Essex. Shortly after dad was promoted to Flight/Lieutenant. On the 7th September dad’s father Fred died so he was granted leave.

In October he was in hospital with flu followed by a posting to No 1357 Heavy Conversion Unit at Faldingworth to convert to 4 engine “heavies” and still with the same unit to Sandtoft, going on to No 1 Lancaster Finishing School at Hemswell just before Christmas 1943. Around Christmas dad managed a few days leave down to Castle Gardens, the reason for being released from duty was recorded as “no navigator.”

1944 was to be another momentous year, on finishing Lancaster training the crew was posted to 100 Squadron at RAF Grimsby (Waltham). Back home in Castle Gardens mum was recording heavy air raids in her diary, spending several nights with us twins under the kitchen table.

Training continued and dad flew “2nd dickie” with the C/O of 100 Squadron to Le Clipon on 24th May, followed by the crew’s first Lancaster op solo on 28th May to attack a Field Battery in Northern France. Further ops followed in the run up to D-Day and on the night of the 5th/6th June in what was to become their regular Lanc’ LM 585 HW-S (S-sugar) they took part in the raid on the medium gun battery at St. Martin de Varreville. There was bright moonlight and visibility was excellent, all the aircrews reported seeing the huge armadas – both air and sea – dad’s thoughts must have been with his former pupils in both aircraft/gliders and also of course his brother Guy, down below on HMS Goodall a frigate (destroyer escort) which was escorting HMS Nelson to the Normandy coast, then dashing back to Plymouth then to Mounts Bay Cornwall on submarine patrol then back to Liverpool. Further D-Day ops followed and eventually dad was able to contact mum and report that all was well after about 10 days of total security blackout. Back home there were air raid warnings all through the day and overnight. Dad got a 48 hour pass at the end of June, shortly after leaving for Waltham on his motorbike a V1 landed on Boxhill behind the house, the blast blowing down the scullery door – we were under the kitchen table – thankfully there were no casualties. Soon accommodation was found in Hull and Mum packed to leave once again.

Operations for dad and his crew continued during July, mostly over France to support the invasion, by this time dad had logged over 1100 hours. At about the same time as the failed plot to kill Hitler was announced on July 21st, the allied invasion was getting bogged down so 100 Squadron remained busy with targets in occupied France. On August the 8th 1944 mum noted in her diary “H left early for Waltham” this would be the last time she was to see him for 8 long months. Their regular Lancaster LM585 HW-S (S-sugar) had been lost with another crew at the end of July and having flown a couple of ops on different aircraft they now had a new Lancaster LM658 HW-W fresh from the Avro factory at Yeadon in Yorkshire, also the crew were joined by a new navigator P/O Gerald Hood. Waltham and 100 Squadron had a good friendly reputation and having moved from a neighboring Squadron and aerodrome within 1 Group, Hood would no doubt have quickly felt at home.

On the night of August 12th’13th the target was Braunschweig (Brunswick), dad and crew took off on runway 36 hoping for a lucky run as they joined the bomber stream, they were all well on their way to completing their first tour. The raid itself is well documented and was not a great success, over the target area the aircraft was hit by flack and caught fire, the crew managed to keep things going, possibly diving to try and put out the fire, struggling on until a German night fighter spotted the burning Lanc’ and attacked, (the attacking fighter was identified by the crew as an Me 410 as stated in his report on repatriation to the UK, but this is discounted as an error in the heat of battle by night fighter experts as evidence suggests that no Me 410’s were operational in the area on the night in question). The night fighter inflicted heavy damage to LM658’s control surfaces and the intercom was also shot away, dad’s inability to make contact with the crew at this moment to give the order to bale out was always to haunt him, the aircraft exploded throwing some clear as detailed in the Gerald Hood story.

Dad was thrown clear of the Lancaster and “came to” just in time to pull the ripcord, landing heavily in a field, with injured knees and with a head wound. Alone in the dark, he was near Bergentheim on the Dutch German border and not sure if he was still in Germany he tried to head west but struggling to walk he came across a haystack and burrowed into it to rest, it was about 0400 hrs when he would have expected them all to be safely home. An hour later he found he could not walk and spotting an isolated farmhouse crawled to it and managed to rouse the farmer and his wife who took him in and called a doctor to tend to his wounds, he was very lucky as his new hosts supported the Dutch Resistance and so started his own evasion story.

His evasion report M.I. 9.ISIP.G. (-) 5068 dated 8th May 1945 lists no less than 12 brave men and women of the resistance or helpers who risked betrayal, capture, torture and death for themselves and their families daily to help allied evaders and others. Dad stayed near the village until his wounds healed, on 17th August he was joined by his Flight Engineer Jock Downie and early in September for security reasons the resistance decided to move them, they were to walk down an isolated road until picked up, which they were in a biscuit van which took them to Almelo they then travelled on to Hengelo where they stayed, evading capture until liberated by The Hampshire Regiment on 5th April 1945 .

Liberation day in Hengelo, Harold Paston-Williams is extreme right, middle row, wearing a beret. John Downie is fifth from the left, front row, in hat and light raincoat. Second from the left, front row, in a light raincoat is Roy Fellows, rear gunner of ME732 the 61Squadron Lancaster that crashed on Almelo in Sept 44.

Early on he wrote a pencilled note to mum to be posted by his hosts after the war giving some clues as to what had happened but obviously not in detail, He had many lucky escapes, at one time hiding under a the 4th bunk in a hut, the Germans searched the first 3 but were called away before they got to him . On another occasion he was picked up in disguise by a German truckload of soldiers, he played deaf and dumb and they gave him a lift into town. Although hidden separately he was in touch with Jock Downie and others including a German deserter known as Eduard Alzan and they had several adventures dressed by the wives of their hosts in female attire, both being sufficiently unattractive to ward off amorous soldiers! At one point they were tempted to try and steal an aircraft parked near a factory in Hengelo and fly it home but decided they would probably get shot down as the Allies were advancing! (The full story of their evasion is still being researched in Holland and in the UK).

Back home the news that Dad was missing was sent to Castle Gardens and passed to Mum in Hull. The day LM658 came down mum had been expecting dad back, in time for her birthday on the 14th August, instead of a happy day with us twins the long wait and uncertainty began, helped of course by visits from dad’s squadron C.O, the Padre and of course the family. Day after day the entries in mum’s diary began “no news H,” Then a request to know where to send his clothes and personal effects, As he was posted as missing, dad’s personal kit had to be returned to mum and when his locker was emptied back at Waltham they found a tiny blue velvet shoe (my first) kept as a lucky mascot but not taken with him on that fateful trip, they say the duty W.A.A.F.s cried when they found it! When the personal effects arrived, mum found them comforting and she stayed on in Hull, coping with one year old twins and hoping for the best, but there was no news. However she was encouraged by the knowledge that some crews were making it back after being shot down over occupied Europe. In November she wrote to the next of kin of the rest of the crew. On December 13th she received a letter from the Red Cross stating that Holland, Ramsden, Williams and Watts had lost their lives and David had been captured, but still no news of the other crew members, which of course still gave grounds for hope, Christmas 1944 came and went.

1945 started with a bitter cold spell and lots of snow on both sides of the North Sea, on the 20th of Feb another Red Cross letter confirming burial of the four crew members at Hardenberg but still no other news, so mum decided to head back south to Castle Gardens.

Then finally, on Sunday 9th April a telegram and letter arrived from dad saying he was safe and well! This was followed by a phone call in the afternoon, the following day they were re-united in London, dad had returned home to a very happy family. Later in the month dad went to visit Flt/Lt Holland‘s parents in Horsham and started the first of many trips up to the Air Ministry for debriefings and finding out more of the fate of his crew as information trickled in. He would return very upset as the joy of liberation was replaced by the knowledge of the loss of most of his crew and of course the tragic fate of his navigator Gerald Hood.

V.E. Day came with the tragic news that his brother Guy had been killed on HMS Goodall on the 29th April escorting an empty convoy out of the Kola Inlet in Arctic Russia bound for Liverpool. It was known 13+ ocean going U-Boats were waiting. With others HMS Goodall engaged a U-Boat that had been forced to the surface and then as she turned to engage another she was torpedoed in the port bow where Uncle Guy had his action-station as a coder in the wireless office above the main magazine, the explosion blew the front half of the ship off.

This news further upset dad and he went North for a few days no doubt to try and sort himself out, he returned to his old base at Waltham where he found that 100 Squadron had already moved out and the base was running down. He was later seen in Lincoln Cathedral in what was described as a bit of a daze. Returning home he passed his medical as fit for flying. After a further month of leave he was posted to Wickenby with 12 and 626 Squadrons on” trooping” operations (helping bring the troops home) until the end of the year. He was also accepted into the Caterpillar Club, the exclusive organisation for airmen whose lives have been saved by the parachute.

1946 saw a variety of courses come and go and he finished up as an instructor on Avro Yorks at Dishforth, doing what he loved most, flying. We, the family were still living down in London at that time. 1947 he (and we) left Dishforth in April ending up at Instrument Flying Unit, Pershore where we lived in part of an old farmhouse and as kids we learned to play and help on the farm. Often an occasional York would visit overhead.

1948 -1953 leaving Pershore in February dad moved to the communications flight for Fighter Command based at Bovingdon in Bucks, this was a good move as he could carry on flying and had a lot of freedom when not on call, looking after us and playing Hockey. Sadly, mum contracted polio and after a long stint in hospital emerged breathing, able to use her right arm and hand, little finger of left hand and not much else, despite being wheelchair bound, she carried on bringing us up, She was a great cook and housewife, joining in the service social life as much as she could. During this time many of dad’s contemporaries who had stayed in the RAF were making their way up the career ladder and his log books show his acquaintance with many famous names.

1953 – 1958 and the communications flight job moved to France to be based at Melun Villaroche for Allied Air Forces Central Europe, Fontainebleau, this gave dad another 5 years flexible flying during which time he was promoted to Squadron Leader and C.O of the flight. He also became personal pilot to Sir Basil Embry and in 1953 he was awarded the Air Force Cross (A.F.C.). During this time we lived in a small village in the Forest of Fontainbleau and enjoyed a decent life, albeit on RAF pay which was a lot lower than the salaries of our allies! The village had suffered during the Nazi occupation and as only 8 years had passed since the end of the war, memories were still raw on all sides, though we were made very welcome by the locals.

I was fortunate to be allowed to fly with dad quite a lot as I grew up, learning to fly on instruments whilst I was still too short to see over the top of the instrument panel, when I wasn’t being airsick, which was quite a lot! I was heartily sick in Oxfords, Ansons, Devons and Pembrokes but somehow it didn’t put me off and I came to understand what a natural pilot dad was, he seemed to become part of the aircraft whatever it was and the whole thing just flowed very very smoothly, from start up, to taxi, to takeoff through flight and touchdown, it was a delight to witness and he was in his element.

By the time we had to return to the UK his chances of continuing flying with the RAF were slim and so he left the RAF. After some attempts to make a living on the ground he turned to civilian flying in the growing corporate aviation sector and started a new career aged 47 flying an ex RAF De-Havilland Devon for Hepworth and Grandage Engineering based at Yeadon, Yorkshire, where coincidentally Avro Lancaster LM658 (HW-W) was built, I wonder if he knew .

Alan Paston-Williams (Updated October 2011)

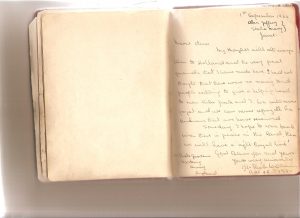

A heartfelt letter from Flt Lt Paston Williams on behalf of him and his fellow downed airmen to Marie Baars-Kroze, one of the key players in the Dutch resistance movement around Hengelo, his well chosen words say so much. (By kind permission of Mnr Leon Baars).

…and a word from the site author:

Throughout my time researching this extended story I have consciously avoided giving any personal opinions on the sequence of events as LM 658 fell to earth that night in August 1944, I had always thought that whatever happened during those final moments as eight young airmen fought for their lives in a blazing aircraft should forever stay between them, but in the summer of 2012 new information was received that cast a new light on events and as the author of their story, I surely owe it to these men to paint as full a picture as possible, in particular, I feel I owe it to the man in command…”Bill” Paston-Williams:

There comes a point where a stricken aircraft can no longer be flown and it begins its fall to earth, at this point, the pilot has little or no influence on the control surfaces and can do no more than try to hold her steady and give the order to abandon. From then on, who lives (if anyone) and who dies is down to a cruel mix of luck and fate, influenced by countless other factors. Now I don’t pretend to understand blast dynamics and the associated laws of physics that apply but what I have learned from both reading accounts and talking to those who do know is that when exposed to an explosion a human body can be vaporized, shattered, internally damaged, superficially injured, merely stunned or blown clear without a hint of injury in what is a macabre lottery, the final moments of LM 658 are a stark illustration of this.

One of the hardest things to bear for the commander of a downed aircraft is to survive when a number of his crewmates perish, especially when they are men you have trained with and bonded with as friends. For this is exactly what happened here and the situation weighed heavily on Bill until his dying day, despite the reality that he had done all he could and no blame could be attached to him, an easy thing to say but much harder to accept for the skipper concerned. The “what ifs” troubled him on a daily basis… “If only I had given the order to go just a little sooner, maybe they would all have got clear” Despite his innermost feelings of regret this professional pilot kept on doing what he did best…..flying, carving out a successful post war career in aviation, but always mindful of the friends he lost on the night when fate decided that he would survive and others would not. Survivor guilt is a common phenomenon amongst former WWII Bomber Command aircrew, I have encountered it many times, a condition made harder to bear by the fact that this generation were forged in the heat of war never to let such thoughts and feelings ever see the light of day.

As skipper, Bill Paston-Williams had no doubt they were in trouble, but his train of thought was clear, to keep the stricken aircraft in the air for as long as possible, to ensure his crew baled out over occupied Holland and give them the best chance of survival, help and eventual return home, in the event the aircraft had indeed just crossed the border from Germany into Holland when control was finally lost. I am sure all who read this can only agree that the skipper did right by his crew in circumstances that we can only begin to imagine, bearing in mind that those of us who have never experienced being aboard a burning aircraft have no right to analyse any further and no right to criticise at all. It is also clear from the facts that the crew all remained at their posts and fought together for their lives until the flames and fumes forced them to move forward when there was nothing else left to do but attempt an escape. Tragically, Bill’s signal to jump came a few seconds too late for the three who were somehow knocked out as they exited the aircraft and never regained consciousness in time to deploy their chutes, the fourth fatality being the wireless operator who lost his battle against the powerful g-forces and was still half way out of the escape hatch when the fuselage section struck the ground.

Of the four that survived the pilot and flight engineer were both stunned but blown clear, regaining consciousness just in time to pull their chutes, the navigator escaped successfully with burns only to meet his tragic end some months later. Finally, the rear gunner who I suspect would have been cut off by a wall of flame and made his successful escape via the rear hatch or even his turret. So in summary the picture I paint is of a skipper who remained in command and a crew who remained at their posts as they faced the imminent prospect of death, the facts support this!

Many years later, when due to illness his time finally came, Bill Paston-William’s last words to his son Alan were “I hope you are proud of me!”… Alan’s reply can remain unspoken here, because lets face it who could think of a reason not to be proud!

I have no authority to write this airman’s epitaph but I hope Bill would see the above as at very least a gesture of respect to the skipper of Lancaster LM 658 whose actions on that night will forever stand up to scrutiny with unquestionable honour.

Alan Barrow 2011 (Revised September 2012)

In memory of:

Squadron Leader Harold (“Bill”) Paston-Williams AFC 1911-1976